Bill Lair: Dispatches From the Edges of a Hidden Conflict

Lair: Alliances, Sacrifice, Hidden War.

The landscape of covert operations is, by its very nature, one of shadows and calculated ambiguities. Yet, within this realm of clandestine engagement, certain individuals emerge whose actions illuminate the intricate mechanics and profound human costs of proxy wars. William "Bill" Lair was one such figure, an American intelligence officer whose extensive career in Southeast Asia, particularly his deep and often unconventional entanglement in Laos's "Secret War," offers a stark, unvarnished look at the ground-level realities of Cold War strategy. This account aims to dissect Lair's operational philosophy and his unique relationships, providing a detailed historical record without romanticizing conflict or attempting to encompass the rich and multifaceted identity of the Hmong people, whose narrative extends far beyond this particular historical intersection.

Born on July 4, 1924, in Hilton, Oklahoma, William Lair’s formative years were a study in adaptation and resilience, shaped by the harsh economic climate of the Great Depression and a childhood marked by frequent relocation and financial strain. These early experiences forged a pragmatic self-reliance that would define his later work. Growing up in the Texas Panhandle, amidst the rough-and-tumble of ranching and early oil boomtowns like Borger, Lair developed a keen sense of observation and a capacity for problem-solving in challenging environments. He absorbed critical lessons from his mother, who relentlessly pursued education for her children despite being widowed, and from his grandfather, a quintessential Western figure who imparted the subtle art of influencing people through rapport rather than direct command – a skill Lair later deemed essential for any effective intelligence officer. This upbringing fostered an early, genuine empathy for "primitive" people, a quality that would uniquely position him in cross-cultural intelligence work.

The outbreak of World War II served as Lair's brutal proving ground. He enlisted in 1942, choosing the armored force, a decision he credited to a recruiter's pitch about its elite nature. His service in the 3rd Armored Division in Europe exposed him to relentless combat, from the hedgerows of Normandy to the brutal winter fighting of the Battle of the Bulge. Lair’s experience as part of a mortar platoon in a tank battalion offered a unique vantage point on the war’s mechanics and survival. He witnessed firsthand the stark reality that "motivation is everything" in combat, and that small, cohesive units operating with initiative often outperformed larger, more conventional forces. He recounted a memorable instance where his three-man squad, exploiting surprise and a sergeant's German language skills, managed to capture 35 German soldiers, demonstrating the power of unconventional tactics over brute force. These direct, often visceral, lessons in adaptability, unit cohesion, and pragmatic improvisation in the face of chaos became the bedrock of his later operational philosophy.

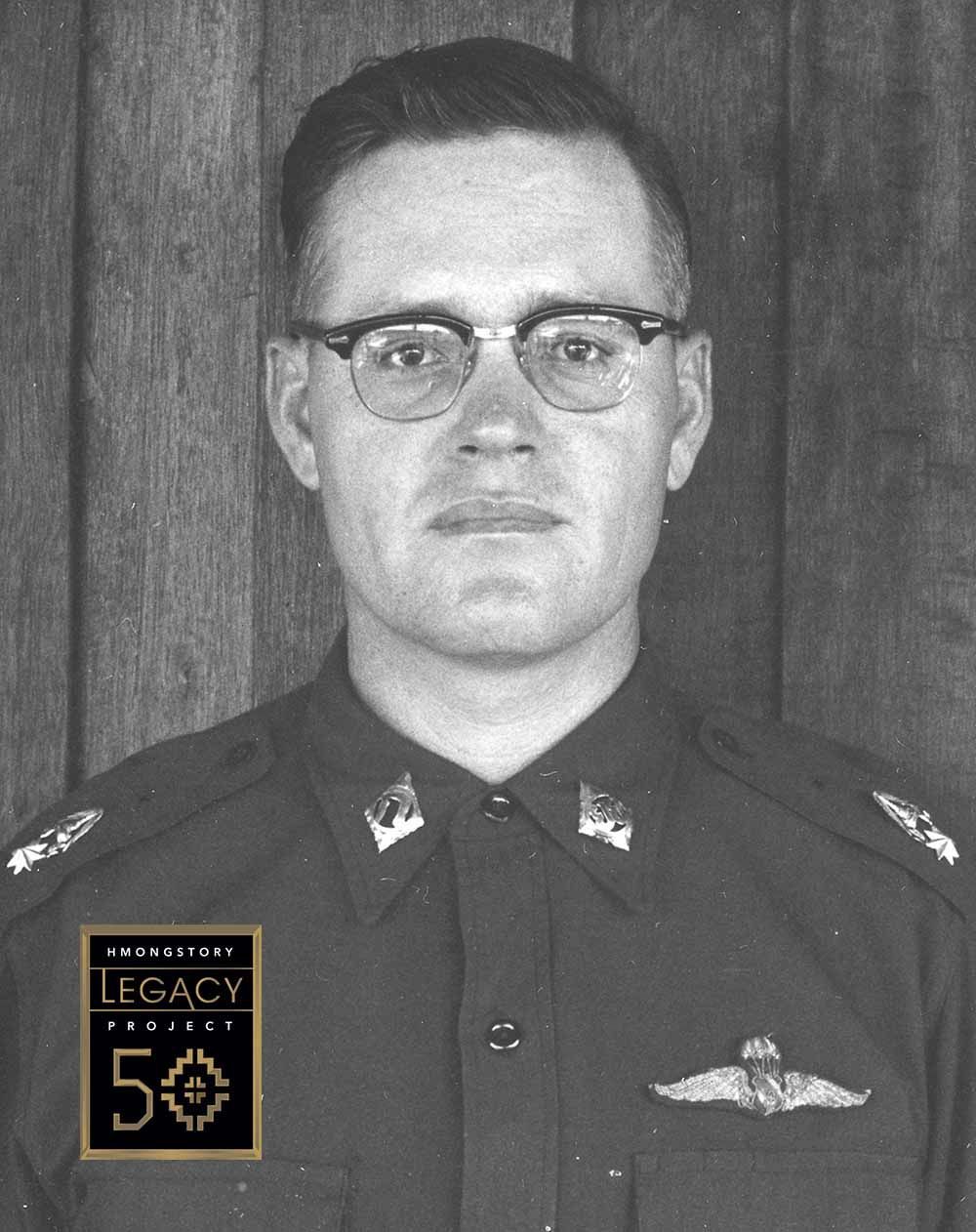

Following his graduation from Texas A&M in 1950, with the Korean War looming, Lair sought a path that blended his wartime experience with his desire to counter communist expansion without being drawn into conventional ground combat. He found this opportunity in the newly formed Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), joining as part of its first class of Junior Officer Trainees (JOTs). His intensive paramilitary training equipped him with specialized skills, and despite his expressed preference for other regions, Lair was assigned to Southeast Asia in 1951. This posting, initially under the cover of the Southeast Asia Supply Company (SEA Supply), would define the majority of his career.

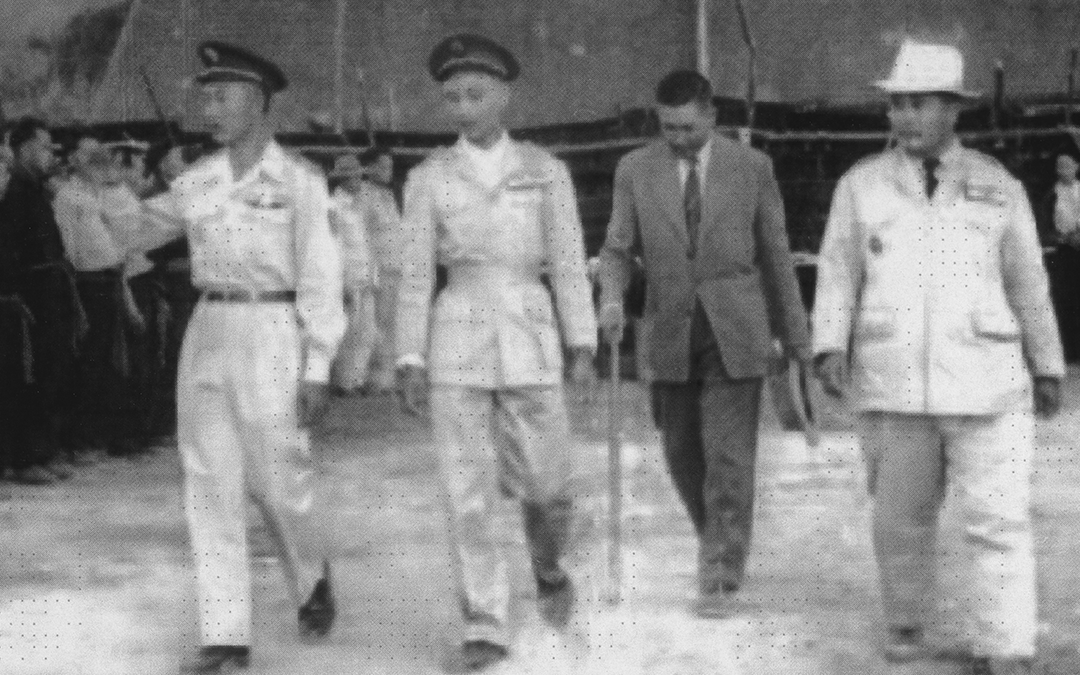

Lair's early years in Thailand were marked by a deliberate and comprehensive immersion in the local culture. He swiftly learned Thai and actively embraced the challenging living conditions of his Thai counterparts, a stark contrast to the detachment often observed in Western advisors. This direct engagement fostered a profound level of trust and respect, earning him a reputation among the Thai as "the man who never lies". A pivotal achievement of this period was his instrumental role in establishing and developing the Police Aerial Reinforcement Unit (PARU) alongside Captain Saneh Sittiphan of the Thai National Police. Lair eschewed traditional hierarchical advisory models, instead cultivating a truly "collegial style" of partnership. He championed the recruitment of officers from the enlisted ranks based on merit and demonstrated motivation, rather than social standing—a radical departure from established Thai military norms—which significantly enhanced the unit's effectiveness and esprit de corps. His commitment to this partnership was underscored by his unique status as a commissioned officer in the Thai National Police, a symbolic act that deepened his integration and solidified trust. Further cementing his ties to the nation, Lair married Chalern Savetsila, a Thai woman from a prominent family, providing him with invaluable cultural insights and a network that would prove crucial in navigating complex political landscapes.

The 1957 coup d'état in Thailand, which saw General Sarit Thanarat assume power, presented an immediate existential threat to PARU due to its close association with the ousted General Phao. Despite the ensuing political upheaval and initial attempts by the new military government to dismantle the unit, Lair, working in concert with his trusted Thai colleague Pranet Ritruechai, meticulously navigated this treacherous political environment. Their persistent efforts, bolstered by subtle royal endorsement and PARU's undeniable operational effectiveness, ultimately secured the unit's survival. The unit was subsequently rebranded as the Police Aerial Reinforcement Unit (PARU), a less politically charged designation that allowed it to continue its work. Lair's professional bond with Pranet Ritruechai matured into a profound personal friendship, characterized by "unconditional mutual trust" and a shared understanding of PARU's unique mission. This deep rapport allowed them to operate with remarkable autonomy, making decisions and executing actions that served both Thai and U.S. interests, even if it meant navigating around traditional bureaucratic channels or official directives.

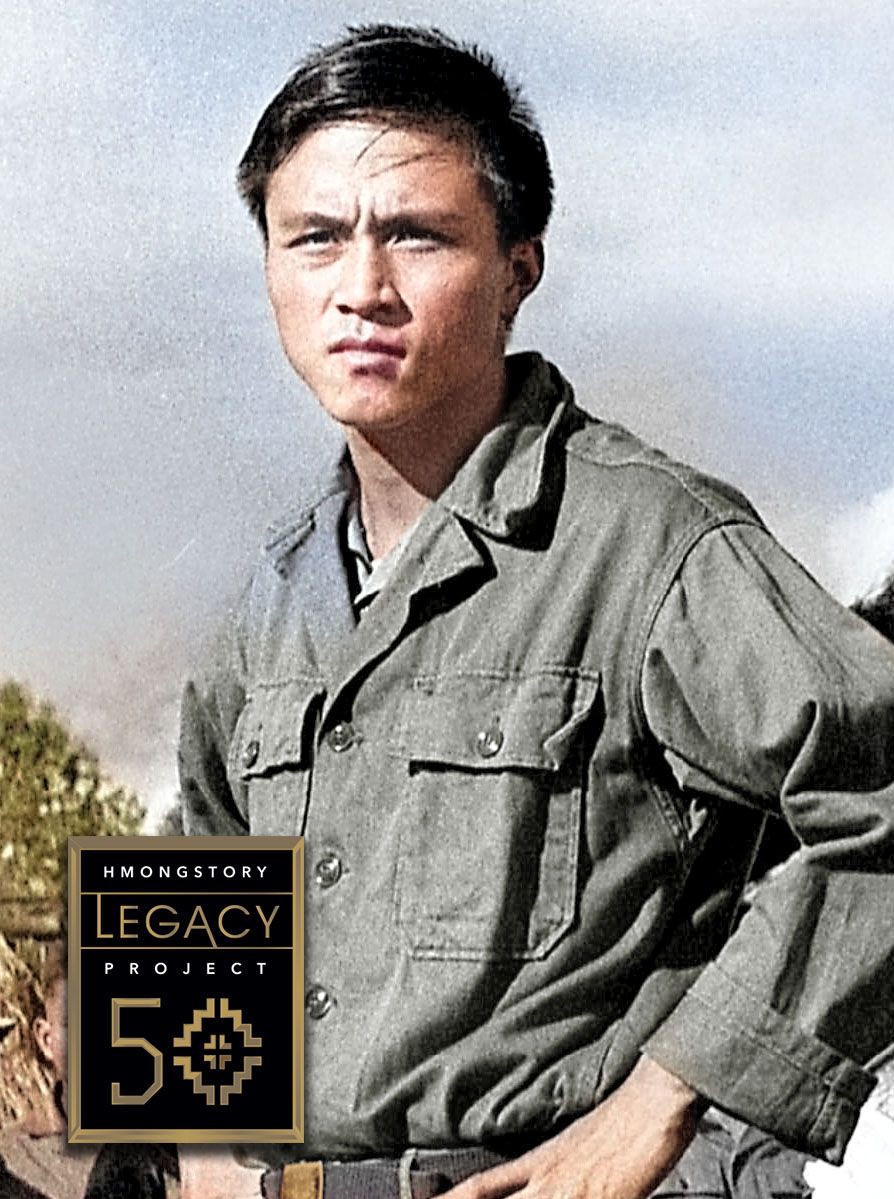

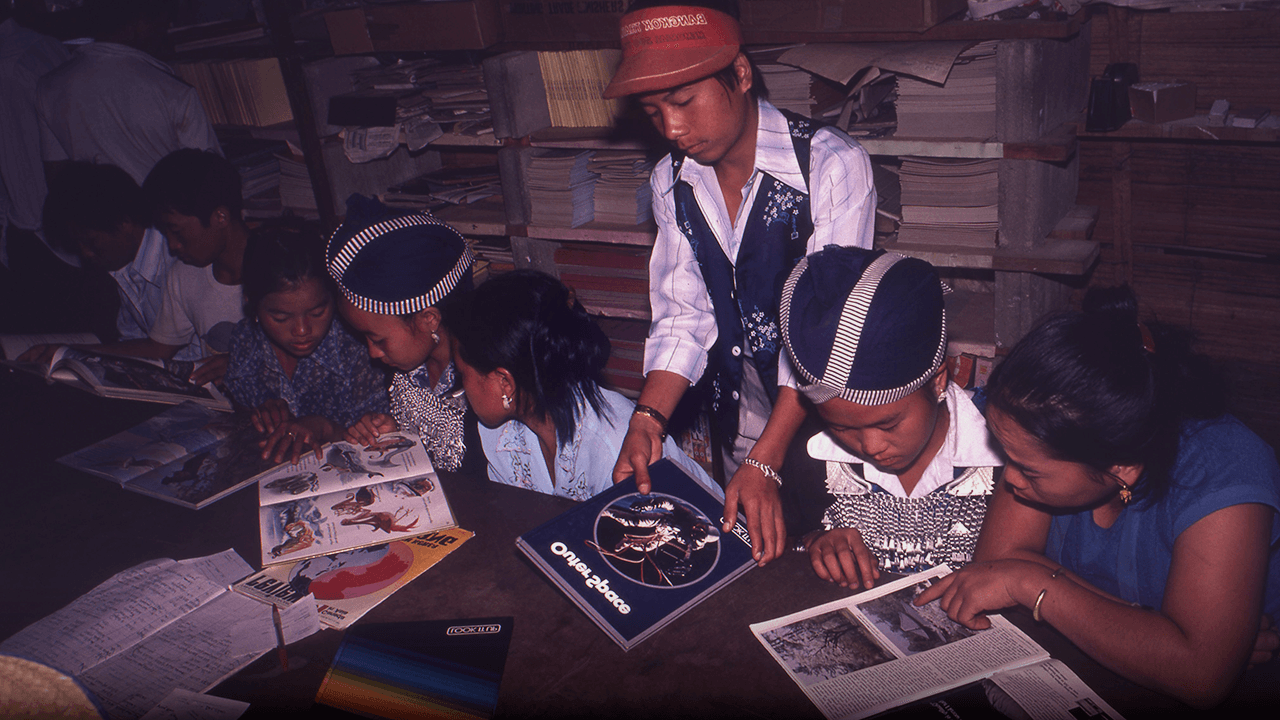

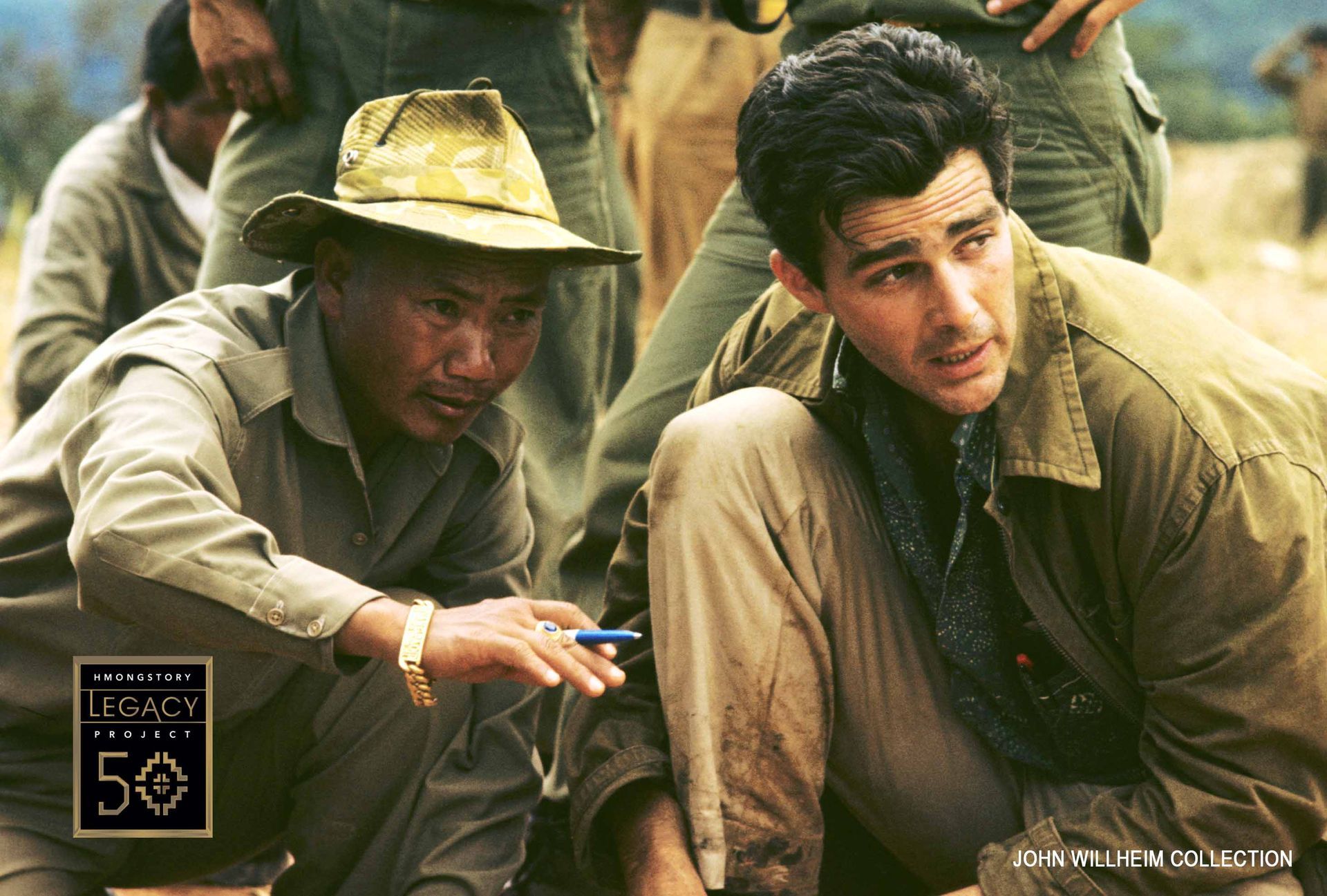

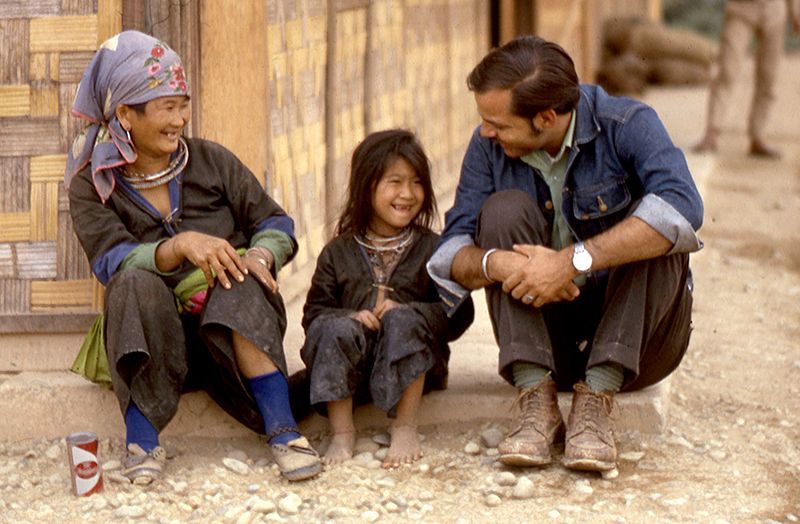

As the geopolitical situation in Southeast Asia continued its inexorable decline, Lair's specialized expertise became critically important. In late 1960 and early 1961, amidst the escalating chaos in neighboring Laos, he astutely recognized the inherent weaknesses of the Royal Lao Army. He proposed a bold and unconventional strategy: arming and training the Hmong hill tribes as an indigenous guerrilla force to counter the expanding influence of the Pathet Lao and their North Vietnamese allies. This initiative marked the true genesis of the U.S. involvement in what would become known as the "Secret War" in Laos. Lair quickly established a profound and enduring working relationship with General Vang Pao (GVP), the charismatic Hmong leader. Lair viewed Vang Pao as the ideal figure to mobilize and lead his people, emphasizing the critical importance of empowering local leadership rather than imposing American command structures. Lair's operational philosophy in Laos remained consistent: maintain a low U.S. profile, directly support indigenous forces, and focus on flexible guerrilla tactics to effectively tie down larger North Vietnamese units. He meticulously oversaw the rapid expansion and training of Hmong irregulars, provided essential logistical support through innovative methods, and even initiated a pioneering program to train Hmong pilots for close air support, anticipating the long-term need for Hmong self-sufficiency in air operations. He consistently ensured that the Hmong's primary motivation stemmed from their determination to protect themselves and their families from Pathet Lao and North Vietnamese oppression, rather than any externally imposed ideology.

However, as the Vietnam War intensified and the broader U.S. commitment in the region escalated, Lair found his operational philosophy increasingly at odds with Washington's evolving directives. This tension was particularly pronounced under Ambassador William Sullivan, who arrived in Laos in December 1964. Sullivan and the broader U.S. foreign policy establishment began pushing for more conventional military engagements and a larger, more overt American presence. Lair consistently voiced his concerns that this strategic shift would undermine the effective guerrilla warfare strategy he had painstakingly built, leading to unsustainable casualties among the Hmong. He maintained that the U.S. was fundamentally misjudging the nature of the conflict and the capabilities of its allies, losing sight of the core principles of irregular warfare.

A stark and personally distressing illustration of this strategic divergence was the disastrous Battle of Nam Bac in late 1967 and early 1968. Despite Lair's emphatic warnings against a fixed, conventional defense—arguing it would create a "very inviting target" for the North Vietnamese Army due to logistical vulnerabilities—the U.S. country team reportedly chose to proceed. The outcome was catastrophic: six Lao battalions were decimated, marking the largest single loss for the Royal Lao Army. This event profoundly distressed Lair, who felt his strategic judgment had been ignored. The accelerating "conventionalization" of the war in Laos, coupled with the increasing disregard for his unique expertise, ultimately contributed to Lair's decision to depart Laos in 1968. He concluded that the original, effective concept of guerrilla warfare was being abandoned in favor of a conventional approach ill-suited to the rugged terrain and the nuanced nature of the conflict.

Following a tour at CIA Headquarters in the U.S., Lair returned to Bangkok in 1970 as Deputy Chief for Special Activities. In this role, he continued to leverage his extensive network and profound understanding of Thai politics to facilitate critical operations, including negotiating the terms of expanded Thai military involvement in Laos. He also played a key role in significant counter-narcotics efforts, notably orchestrating the covert capture of major drug lord Lo Sing Han within Thailand, a testament to his enduring ability to operate effectively and discreetly at the highest levels of foreign liaison. William Lair remained in Thailand until his retirement from the CIA in 1977.

In his retirement, Lair reflected candidly on the "victories and defeats" of his long and impactful career. While acknowledging the tragic ultimate outcome for many Hmong following the fall of Laos, he also recognized the success in containing the conflict within Laos, thereby preventing its spillover into Thailand, a primary objective for the Thai government. He maintained that the most important lesson from his decades of operational experience was the immense potential of local populations to manage their own challenges, provided they had the requisite motivation and appropriate external support. His philosophy, rooted in the belief that "we don't solve it" for them, but rather enable them, became a guiding principle he articulated consistently throughout his life.

Lair's legacy: a master of surrogate warfare, built on cultural understanding, deep trust, and unconventional pragmatism.

References

- Lair, J. W. (n.d.-a). Interview with Bill Lair (S. Maxner, Interviewer). The Vietnam Archive at Texas Tech University.

- Lair, J. W., & Ahern, T. L., Jr. (n.d.-b). An "excellent idea!": Leading surrogate warfare in Southeast Asia, 1951-1970 - A personal account. Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency.