The Ghost of Phou Pha Lang

A-26 Navigator's Unforgettable Encounter with Tallman,

the Hmong Hero of Laos

In the hushed, undeclared war fought over the unforgiving highlands and deep jungles of Laos during the Vietnam War, an old warrior was given new teeth. The Douglas A-26 Invader, a twin-engine attack bomber forged in the crucible of World War II, was resurrected and fiercely reborn as the A-26A Nimrod.

From 1966 to 1969, these formidable aircraft, flown by dedicated Air Commando crews, became a sharp instrument in the desperate effort to stem the flow of men and materiel down the Ho Chi Minh Trail. This was no conventional air campaign; it was a highly specialized, often nocturnal, battle of wits and firepower waged against a tenacious and ghost-like enemy.

The journey of the A-26 to its "Nimrod" call sign above Southeast Asia was a long and storied one. It had first tasted combat in the closing years of World War II, quickly lauded as a potent light attack bomber. After the war, it remained a stalwart of the U.S. Air Force's light bombardment squadrons. A notable designation change occurred in 1948: after the Martin B-26 Marauder was retired, the Douglas A-26 Invader was re-designated the B-26B to prevent confusion. In this new guise, it saw extensive action during the Korean War, primarily mastering the challenging night interdiction role, flying over 12,000 sorties.

The early 1960s saw the B-26 find a new calling in the shadowy world of special operations, including early, discreet missions in Southeast Asia. However, the demanding operational environment and the relentless stress of combat took their toll on the aging airframes. A critical structural issue emerged: wing spar fatigue, dangerously exacerbated by heavy ordnance loads and the punishing impact of operations from rough, often makeshift, airstrips. A series of tragic, fatal crashes attributed to wing failure in 1963 and early 1964 necessitated the withdrawal of the existing B-26s from combat in the region.

Yet, the unique capabilities of the airframe—its endurance, payload, and inherent toughness—were too valuable to abandon. In 1963, even as the older models faced their operational nadir, the Air Force contracted On Mark Engineering Company to undertake a comprehensive rebuild and modification program. This was no mere refurbishment; it was a radical transformation. The resulting aircraft, initially designated B-26K, featured completely redesigned and significantly strengthened wings, powerful Pratt & Whitney R-2800-52W water-injected engines providing a surge of new power, permanent wingtip fuel tanks for extended reach, eight hardpoints under the wings for a versatile weapons load, a standardized nose bristling with eight .50 caliber machine guns, and an updated cockpit with improved avionics.

When these revitalized machines were deployed to Southeast Asia for Operation Big Eagle in June 1966, the designation was officially changed again, this time to A-26A. There were two compelling reasons for this: first, the extensive On Mark modifications had effectively reconfigured the aircraft as a dedicated attack weapon system, making the 'A' (for Attack) prefix more accurately descriptive of its intended role than 'B' (for Bomber).

A Headquarters Air Force memorandum from March 29, 1965, supported this reclassification. Second, a sensitive diplomatic agreement with the government of Thailand prohibited the basing of "bombers" on Thai soil. As the A-26As were to be stationed at Nakhon Phanom RTAFB in Thailand, the 'A' designation deftly navigated this political constraint. Once in theater, the pilots adopted "Nimrod" as their radio call sign, a name that quickly became the aircraft's evocative and widely recognized moniker.

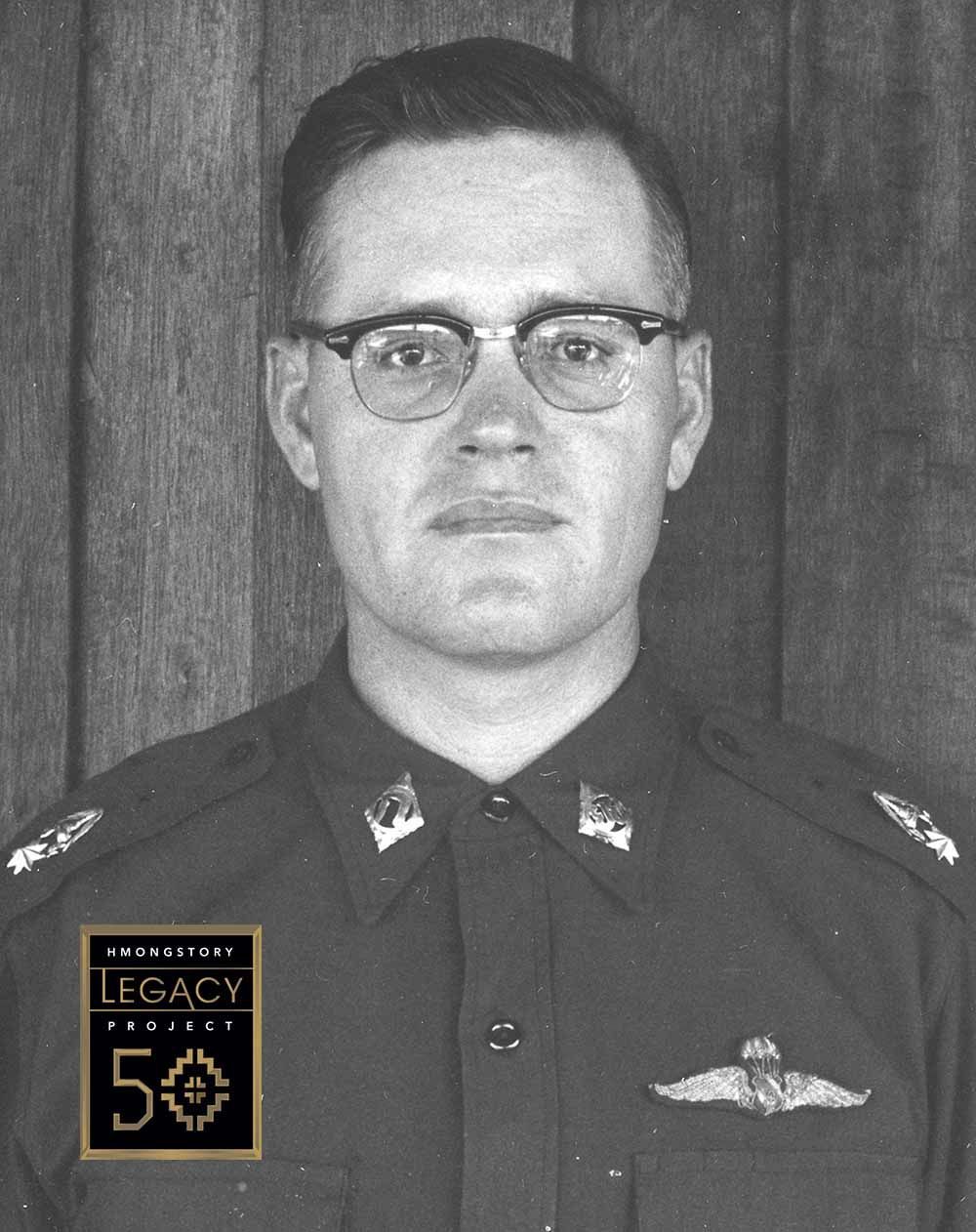

It was into this intense, demanding chapter that Major Frank Hayes (Ret.), then a young navigator, found himself immersed. In 1966, he was part of Operation Big Eagle. His Air Commando unit was already seasoned, having flown the A-26 in various capacities for years. In the fall of 1966, their operations gained a critical new dimension as they began direct coordination with General Vang Pao’s Hmong forces, tapping into his invaluable intelligence network. This crucial collaboration brought American aircrews into contact with remarkable, brave individuals on the ground, none more indelibly etched in memory, perhaps, than the man known by the callsign: Tallman.

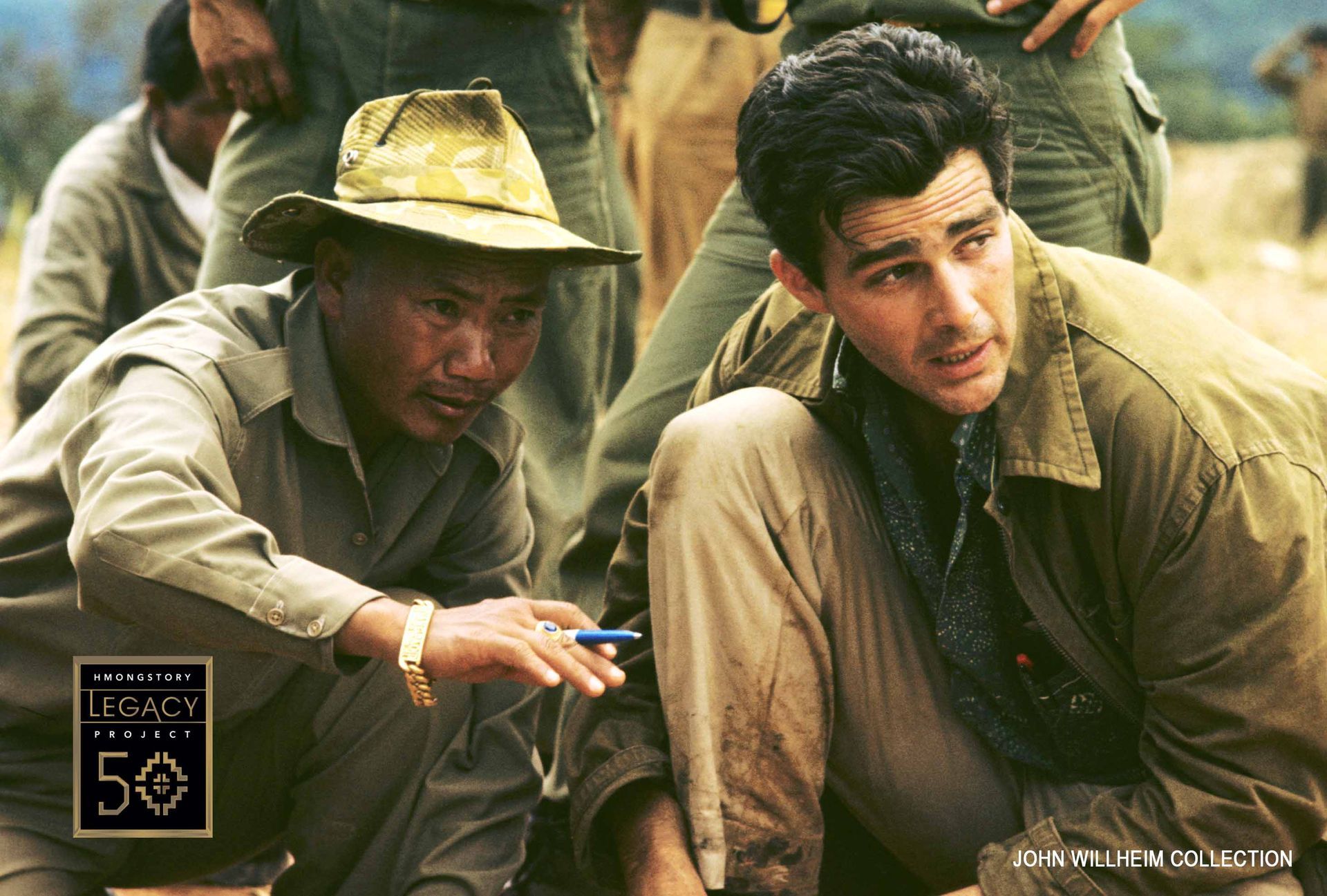

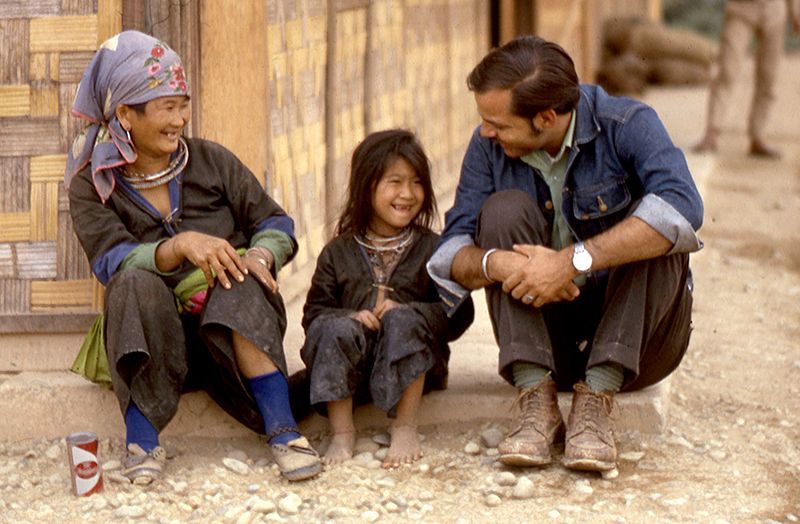

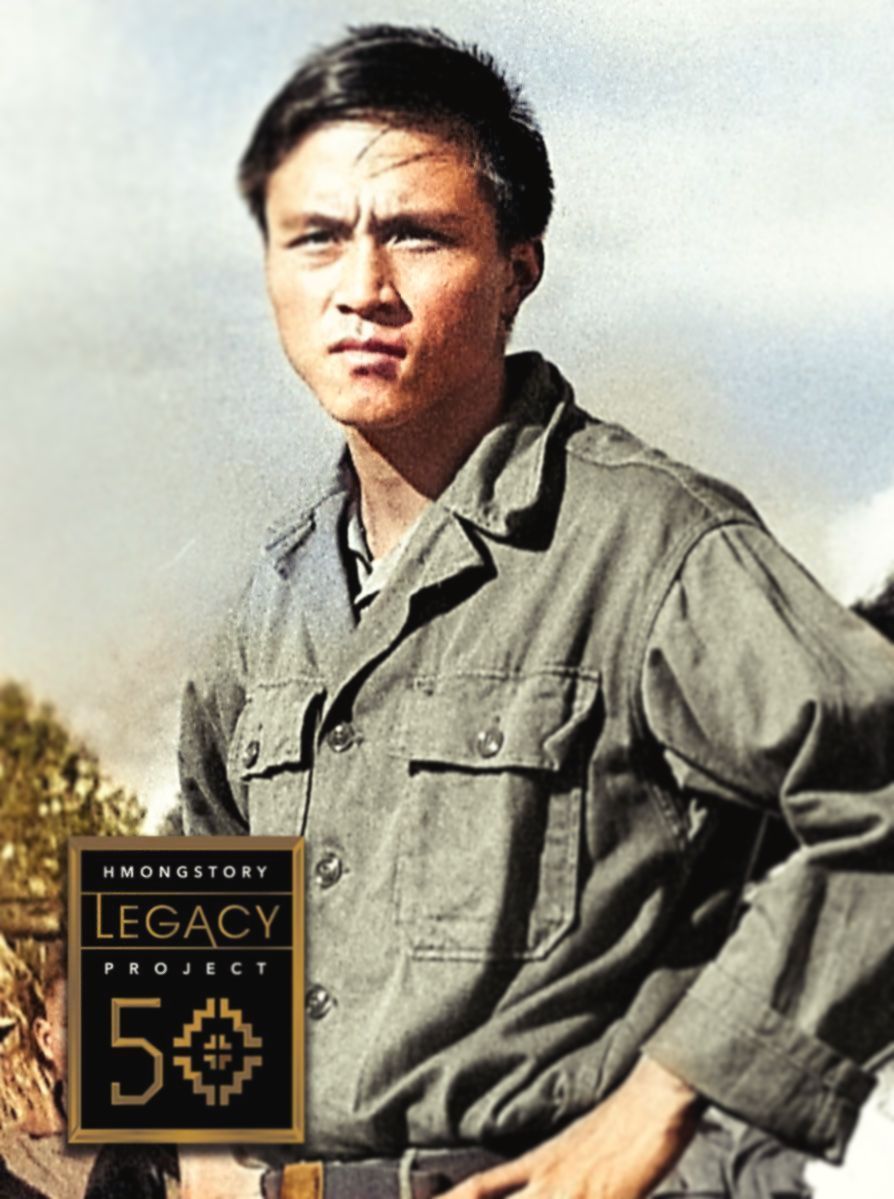

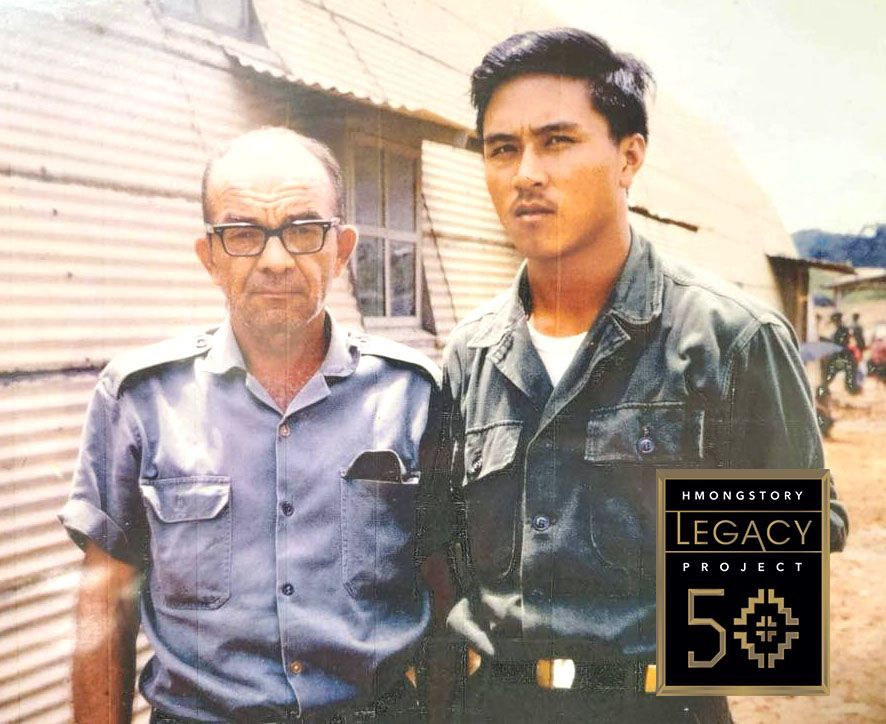

Tallman’s true name was Moua Choung. Unusually tall for a Hmong, the callsign was a fitting descriptor. He had learned English from missionary workers, a skill whose origins were a quiet mystery at the time, but which enabled him to become an irreplaceable bridge between cultures and fighting forces. Recommended by General Vang Pao himself, Moua Choung was the very first Hmong Forward Air Guide. His connections were deep; he was a trusted friend and translator for Edgar "Pop" Buell when the legendary American aid worker first set foot in Laos. Moua Choung established a vital, clandestine base on a formidable mountain called Phou Pha Lang, just south of Sam Neua city—so perilously close to enemy territory that on a clear day, one could glimpse the Sam Neua valley from its summit. From this precarious outpost, he orchestrated his road watch teams – small, daring groups of men who monitored enemy truck traffic along the vital arteries of routes 6 and 7. Initially, their reports detailed numbers and movements; later, their role escalated to the high-stakes task of calling in air strikes. The intelligence that flowed from Tallman's network was described by observer Ernest Kuhn as nothing short of "tremendous."

His mountain base, however, inadvertently became a magnet for local villagers, a sanctuary for those desperate to escape communist control. They began flocking to Phou Pha Lang, and this growing civilian presence, while understandable, threatened the operational secrecy vital to Moua Choung’s intelligence work. It was a delicate, complex situation that American personnel, including CIA case officers and AID workers like Kuhn, attempted to manage, gently assisting civilians to move to safer areas so as not to overburden or compromise Moua Choung’s critical mission.

It was against this backdrop of relentless danger, high-stakes intelligence, and profound human complexities that Major Hayes experienced his unforgettable encounter with Tallman. "This was our first mission using Tallman," Major Hayes recounts, the memory cutting through the intervening decades with crystalline clarity. As the navigator, Hayes was the voice connecting the A-26A to the ground. For at least an hour that night, the fate of his aircraft and its mission was inextricably linked to Tallman's calm, steady instructions relayed over the FM radio. "I asked if he had any information on the position of enemy AAA and any truck traffic. Trucks were our primary target."

Tallman’s reply was unhesitating and direct: "He said he would direct us, so we followed his instructions." What unfolded was a remarkable demonstration of trust and unconventional guidance, a disembodied voice leading them with uncanny precision through the black, mountainous expanse. "His directions went like this, 'my man say you head north'." And north they flew, into the unknown. After intervals of five, ten, sometimes fifteen minutes, a new instruction would pierce the static: "my man say head west." This tense ballet continued for perhaps 45 minutes, the A-26A venturing deeper and deeper into the Laotian upcountry, its flight path dictated by the whispers from Tallman’s unseen, courageous operatives on the unforgiving ground below.

Then, the sharp intake of breath, the moment of imminent action. "After some time, he called and said, 'my man say you over truck'."

The A-26A unleashed its parachute flares. "One flare ignited in the trees and the other over a road in a valley, and smack over a truck," Hayes recalls. But the enemy was swift. The truck driver, reacting with desperate speed, "took off and went into a village a few klicks away."

Hayes relayed the frustrating development to Tallman: they had found the truck, but it had vanished into the sanctuary of a village. Tallman’s response was chilling in its precision: "my man say, 'the truck is under the second house from the east on the north side of the road'."

Despite the startling accuracy of the intelligence, the A-26A crew made the difficult but ethically sound decision. "I replied, 'Thanks, but we won't strike it in the village'."

The reply that came back from Tallman, relaying his operative's sentiment, resonated with a quiet, profound gravity: "my man say thank you, his house." The faceless informant on the ground, Tallman’s “man,” with a courage that defies easy comprehension, had pinpointed the enemy vehicle even though it meant identifying his own home as the collateral, the potential sacrifice.

But Tallman’s work for the night was not yet done. He then directed the A-26A west, guiding them toward another target using an ingenious sequence of friendly ground fires, small beacons of resistance in a vast, hostile darkness.

The extraordinary skill and profound bravery Major Hayes witnessed that night were hallmarks of Moua Choung. But Tallman's invaluable contributions to the war effort were to be tragically, and abruptly, silenced.

In the first week of December 1966, a loss that reverberated deeply through the American and Hmong operations in northern Laos occurred. Moua Choung was returning up the treacherous slopes to his headquarters on Phou Pha Lang with his team. The day was cloaked in a disorienting fog and chilling rain. As they ascended the familiar trail, they were attacked – ambushed, or perhaps, in a cruel twist of fate, mistakenly identified as the enemy. Moua Choung was killed.

The official account from the Hmong men positioned on the mountain peak was one of tragic error: they claimed they hadn’t recognized Moua Choung and his team in the poor visibility, believing them to be an enemy force probing their defenses, and had opened fire without confirming their identity. Two or three Hmong who bore some responsibility were brought back to Sam Thong. Upon their arrival, according to Ernest Kuhn, raw grief and anger erupted as mobs descended upon them, beating them brutally until military police managed to intervene and pull them away.

They were reportedly imprisoned for several months and then quietly released; definitive proof of a deliberate assassination, amidst the fog of war and local complexities, could not be established. However, Kuhn also noted that Long Chieng and Sam Thong were cauldrons of rumor and suspicion, rife with whispers of internal power struggles, simmering clan rivalries, and clandestine plots. Moua Choung was becoming an increasingly popular and influential figure, and his death under such opaque and violent circumstances only fed the theories of deadly intrigue.

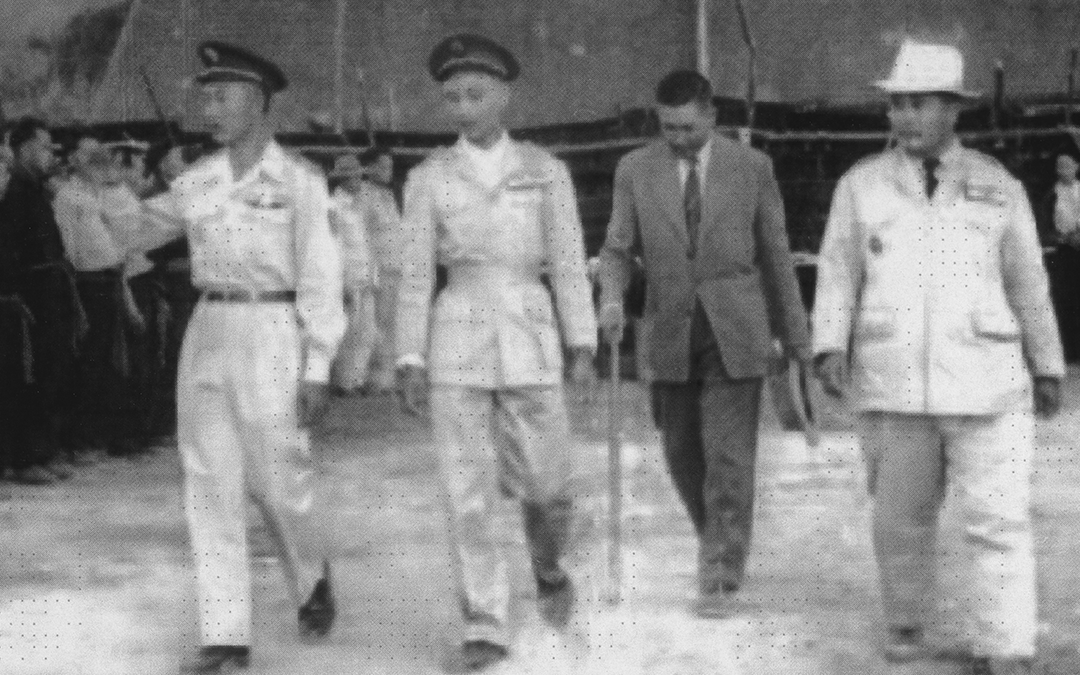

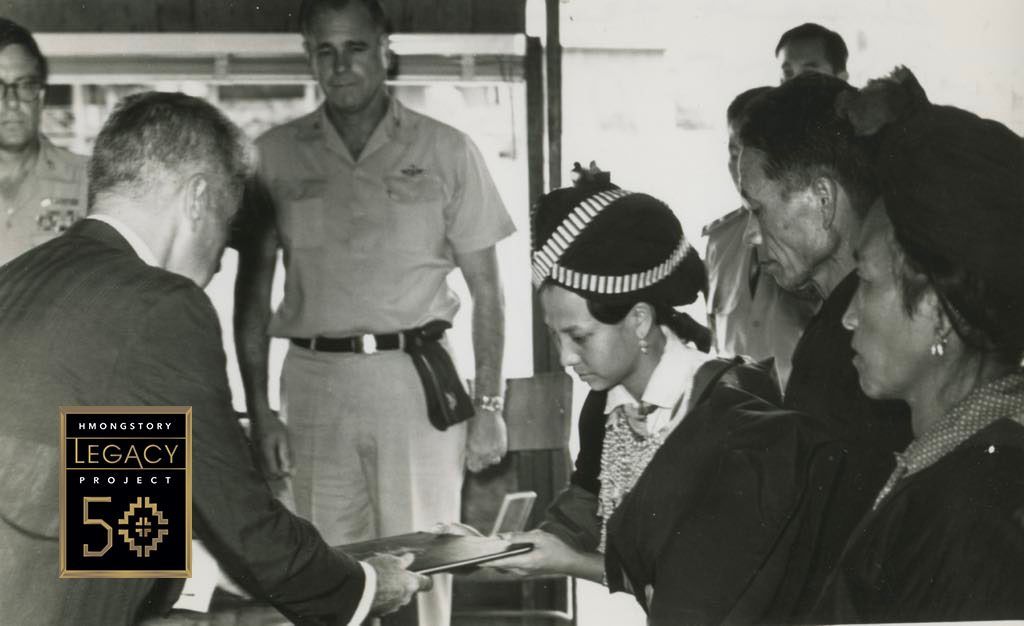

Despite the shadows clinging to the circumstances of his death, Moua Choung's immense service and sacrifice were not, and would not be, forgotten. He was posthumously awarded the Legion of Merit, a testament to his exceptional contributions. The medal was presented to his widow, Maisee Vue, by the then U.S. Ambassador to Laos, William H. Sullivan, at Long Cheng, a moment of solemn recognition. In a final, poignant salute from the skies he had helped to make safer for friendly forces, the U.S. Air Force flew a missing man formation in his honor.

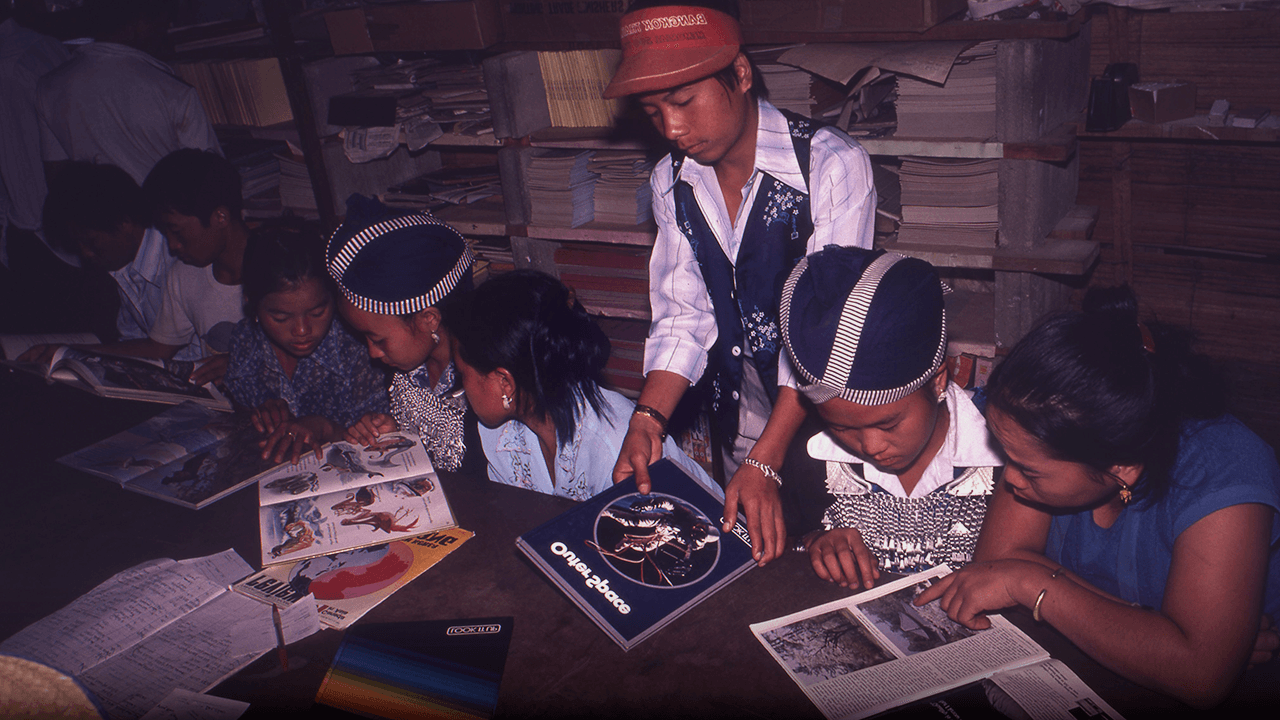

Major Hayes often shares his Tallman story when he speaks to students, using the film Gran Torino as a powerful analogy to bridge the cultural and historical distance. He explains how Clint Eastwood's character in the film comes to understand and respect his Hmong neighbors, learning of their history as steadfast allies of the Americans—a history unknown to so many. Knowing the full, heartbreaking story of Moua Choung – his dedicated service, his quiet bravery, his profound impact, and his untimely, tragic end – lends an even deeper layer of meaning and sorrow to Major Hayes' vivid account. Tallman, the calm voice on the radio, the first Hmong Forward Air Guide, was more than an asset; he was a hero. His courage resonated from the mist-shrouded mountain tops of Laos to the cramped cockpits of the A-26As slicing through the darkness, an unforgettable man who played a crucial, perilous, and ultimately heartbreaking role in a war fought in shadows.